The Holberg Lecture, by Laureate Griselda Pollock

2020 Laureate Griselda Pollock's Holberg Lecture is published here in full.

The full Powerpoint presentation that accompanied this talk, is available here.

Art, Thought and Difficulty

In the abstract for this lecture, I referenced the prefixes: feminist, postcolonial, international, queer, social for histories of art. Are these merely labelling? Or do they signify obligations responding to lived emergencies in our riven and struggling world? Are they the road maps to transdisciplinary encounters in and with art’s histories? Are they incitements to thought? Are they sites of difficulty, of resistance, of transformation?

Each prefix interrogates the others, qualifying their priority and teasing out their entanglement. When, some years ago, I reviewed what I had written by laying out the covers of major books, I saw a picture of what sets my practice apart from the discipline I appear to represent, art history. There are very few monographs — admittedly I have written on named artists such as Mary Cassatt (Charlotte Salomon (1917-43, Bracha L. Ettinger (b.1948) and Vincent van Gog (1857-1890); no period studies — such as Dutch Painting in the Nineteenth Century for instance; no thematic studies such as The Erotic Nude in European Art. I have made no claims for any one artist’s stylistic innovation. What I have done is to generate concepts by means of which to think what I conceived in 1988 as feminist interventions in art’s histories. With Rozsika Parker, I started with the politics of language, taking up Ann Gabhart and Elizabeth Broun’s concept Old Mistresses for their exhibition of 1973 where they exposed the absence of a feminine equivalent to the reverential Old Masters. We qualified it with linking women, art and ideology. Then came Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and the Histories of Art (1988) followed by Avant-garde Gambits: Gender and the Colour of Art History (1993), Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts (1996) a postcolonial intervention, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (1999) and finally The Virtual Feminist Museum (2007 and 2013). This is not a cybernetic or digital museum. The concept addresses the paradox of the museum as the archive of cultural memory where we encounter the past through artefacts and artworks versus feminism-as-still-becoming, still-to-come, taking up the definition of the virtual in a Deleuzian sense of what is not yet fully actualized.

Encounters take place the Virtual Feminist Museum (VFM) in new configurations that challenge the official assemblages of artworks and images pre-scripted according the existing class, race, gender and geopolitical canons of value and exclusion. I also modelled the VFM on the Mnemosyne Bilder Atlas created by the German Jewish art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929), magnificently re-photographed from his original collection of photographs (a story in itself about art history and technology) and exhibited, like some ancient monument, at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin in 2020. Of Warburg’s Atlas of images comprised 63 specially built canvas screens survive and have been reassembled. On the screens Warburg pinned (and often moved) assemblages of photographs of prints, paintings, sculptures, news photos, by means of which he mounted his radical challenge to the dominant trend of his day and to this day, what he termed anesthetizing stylistic art history. Instead, he elaborated a study of symbolic meaning by discerning patterns across images from archaic rituals to contemporary news items in which he defined a study of the image as a pathosformel, a formulation of affective states through which we can trace the migration of deep memory. Images travel and transmit formulations as the mnemonic carrier of once real affections and psychic states. There are given forms formulae— as body gestures, facial expressions and even the agitation of energized accessories that trap psychic forces within ritualized and travelling visual formulae. With this theory Warburg countered western narrative of triumphalism to reveal and explain the otherwise inexplicable, if not contradictory, aesthetic return, at the end of the High Christian Middles Ages in the early modern period progressively/regressively termed Renaissance, to classical pagan pathos formulae.

With the VFM, I seek to trace provisional, situated, resonant and rigorous encounters with and between images of different orders that enable me to tease out the entanglements of historical, social and political processes that are impressed into, inscribed upon, negotiated, and shifted by creative practices of art artist Bracha L Ettinger (b 1948) terms artworking. She adopts and extends Freud’s economic model of the psyche, articulated from 1899 and fully by 1917 as he confronted the horrors and tragedies of industrial world war.

Traumarbeit/Dreamwork, Trauerarbeit/the work of mourning and Durcharbeiten/working through were Freud’s terminology as he abandoned the cathartic for an economic model of the workings of the psyche. Ettinger’s Artworking synthesises the operations of the psyche and the labour of artmaking to propose, for the artist and for culture itself, an ethical obligation to remain with loss and horror, to take on the missed mourning for the specific victims of the second industrial World War within which and distinct from it, was the mass genocide of Jewish and Roma Europeans under a fascist Totalitarianism was matched for the body count by Stalin’s Sovietizing totalitarianism and inhumanity of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The titles of my first two installations — Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive and After-Affect/After-Image: Trauma and Aesthetic Transformation— clearly announce a conceptual rather than a historical vocabulary. A third installation as yet unpublished is Raphael after the Holocaust — what is left of the Western tradition of the image of the body, the mother, the child and the landscape after Hitler, Stalin and Hiroshima?—while the fourth installation takes the form of book I wrote during my Holberg year titled Killing Men and Dying Women: Painting and the Imagi(in)ing of Difference New York in the 1950s which traverses the divisions between the high art of abstract painting and Hollywood’s concurrent exploration of gender, bodies, desire and loss.

In this lecture, I want to perform another installation that distils many themes running across my 50-year project. It will not reveal that my ambition or achievement has not been to rediscover forgotten women artists, as interviewers so often assumed when I was awarded the prize. It has been to forge transdisciplinary modes of art historical cultural analysis that respond to the obligations that the major social movements and histories in which I was formed place upon the thinking scholar. What follows will not look like art history of great white male artists or even with added great white women artists. It seeks to conjugate complex relations of difference and specificity, injury and creativity.

This is a photograph taken in 1950. It is a beach scene with women and children on holiday at the seaside. It is also an inscription of a political history, even a concentrationary history. Finally, it is a site of affect, perennial anguish, longing and troubled mourning both personal and political.

It is, as you will have guessed, a family photograph, a type we have learned to consider seriously though the work of British artist-photographer Jo Spence (1934-1992). In her exhibition Beyond the Family Album, 1979 Spence initiated a working-class feminist analysis of and through domestic photography the year before French cultural theorist Roland Barthes (1915-80) positioned a photograph he would not illustrate from his family album, a photograph of the recently deceased mother as a child, the mother beside whom he had lived his entire life, at the heart of what has become an influential study of the traumatic charge of the photograph. Barthes introduced the twin concepts of studium—referring public and historically discoverable knowledge—and punctum marking the traumatic element in a photograph to incite individualized affect.

In 1980, the American photography and cultural scholar Julia (not Marianne) Hirsch argued that we must family photographs as signs, even as allegories. [1]

Lumps of experience, rites of passage, grains of poignancy and promise: all of these turn us into artists sorting through life in search of shapes and events which our cameras will turn into symbols and allegories. The sleeping child, the fleshy mother, the tired father, the testy siblings, can, in the quick eye of the camera, be transformed into images of innocence, protectiveness, enterprise and sharing. Family photography is not only an accessory to our deepest longings and regrets; it is also a set of visual rules that shape our experience and memory. [2]

In my one major monograph, Charlotte Salomon in the Theatre of Memory (2018) I cited Julia Hirsch’s words to frame my assemblage of the few surviving family photographs that remain to chart the shortened life of the artist Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943), whose life, death and her single monumental artwork, Leben? oder Theater? (1941-42) dad occupied my thoughts for over 24 years, of which 15 had been spent trying to figure out how to write a book in which all three—her life, her death and her artworking —collided at the heart of the terror and horror that was the Third Reich and under the shadow of domestic sexual abuse.

We can read across these photographs something about a nine-year-old child without a mother, a daughter who lived alone with her father cared for by multiple governesses, a young adult who had to get a passport to escape from Germany in 1938 to love with exiled grandparents in the South of France where she dedicated herself to painting for which right she had to apply as a stateless person for a regularly updated permit to reside, temporarily. These domestic and institutionally-inflected images capture moments of time in one family. They can be also read as allegories of a ruined childhood, maternal absence, forced exile and artmaking. By what is lacking is any image of the artist beyond her mid-twenties. This absence forces us to confront the invisible fact of the brutally and politically and racially shortened life of a Jewish woman murdered by her own state at the age of 26, and in Auschwitz on 10 October 1943. The Stolperstein, the stumbling stone as memorial set in the pavement outside her childhood home in Wielandstrasse, Berlin lists the locations of her life under the Third Reich and her terrible dying exiled to France, incarcerated in a camp called Gurs, deported to Drancy and murdered in Auschwitz.

The photograph with which I have opened this lecture invites and justifies a reading that does has neither the historic nor the tragic grandeur of images of Charlotte Salomon, artist and Jewish victim of a heinous genocide. Yet it shares something of the politics of terror that underlies both that I shall tease out over the lecture.

I can locate this photograph on the beach at St Michael’s-on-Sea in what was then Natal (named so by the Portugese Vasco da Gama (1460s-1524) because he arrived on 25 December), now named Kwa-Zulu-Natal province. A map of this coast reveals the worlding (Gayatri Spivak’s key concept for im. We find English seaside resorts’ names such Ramsgate, Margate or very British referenes to Trafalgar and Port Edward and even Oslo Beach: all holiday resorts.

This is conventionally a holiday snap, probably taken by an unseen father, who at this date 1950 was the man assumed to own the camera and have the technical know-how. The photograph captures the ramrod straight back of a toddler, protected against the cold of the beach (this is August in the Southern Hemisphere) with a knitted woollen cardigan. Her blonde hair is bobbed in what is known as a pudding basin cut. I think it must be a girl.

The full height of the seated toddler just reaches the head of the adult woman, stretched out on the beach, her body invisible, but propping herself up on her elbow as she watches whatever it is, unseen, that the child is doing. Despite this curious incarnation of the duet of mother and child on a beach holiday, which is the feature I presume the photographer has wanted to capture—the tender moment of his child and his wife perhaps, — the wide angle of the scene captures another adult woman and two other children at a distance off to the right. They are not a family. This is not an image of mother and children image, or is it?

The African woman is seen frontally. She is fully dressed, in a uniform, the black dress and white apron required of or imposed on African men and women who worked as servants for white people in this country. Unusually, she is not wearing a cap. The African woman is in charge of two white children in a world where she is named ‘a black’. She is sitting on a beach where, ‘as a black’, she is not allowed, except in uniform and where she cannot swim in this sea.

What arrests me as I look at the photo is that the African woman is looking at the invisible white man taking the photograph. Is it curiosity or something else? The quality and calibration of the photographic film to register light on white skins itself makes it difficult to discern her features clearly. Racing is occurring before our eyes. Race politics is a matter of technology.

The gazes of the white mother and the white child on the left, who both must be thus named so for the child’s blondeness and the mother’s sharp profile and bathing costume,are both occluded. They are the object of another’s vision and this visualization of the allegory of mother and child, even of o inclination in feminist philosopher Adriana Cavarero’s thesis on the geometry of gender in Western thought and representation (2016). The African woman’s presence and her look shatter the potential of the enclosed and deeply rooted, if also ideological, image of Mother and Child. Her gaze relativises its naturalness and endlessly poses a question also to us in this moment of our encounter with it.

She is possibly, probably, also a mother. But her children cannot come to this beach and sit. They must sit on a stony beach set aside for black and coloured people. This sandy beach is for whites only and for those who become invisible as people because they are the white family’s unnamed or nameless servants. The children of this African woman are probably living a thousand kilometres away in a rural area, in a reservation known later as a Bantustan, to which African families who have so long inhabited this continent were expelled during the Apartheid regime. She may see her loved ones with luck once a year and never watch each tiny development of her child that the white mother here has leisure to observe.

Even as I have gazed, for many years, in anguished mourning, at this image of my childish self in proximity to my mother who died very young, I realized I was also being embedded in a political image shaped by the historical process that had placed me on this beach in a country that marked my identity and whose history shapes my obligations as a scholar. Here, in this image, I read the history of the Second World War that drove my parents in 1947 to South Africa to escape the post-war cold (the great freeze of 1947) and the post-war economic chaos of post-war Britain. I also read the longer history of European colonization that made Southern Africa available as a destination for two British immigrants to a country where they would find professional jobs that made possible beach holidays at hotels with golf courses and rooms for servants and nannies, white and black. They had arrived just as the 1948 election victory of the nationalist Party lead to the declaration of the formal policy of Apartheid, the segregation of the races, just two years before this photograph was taken. The entanglement of race and gender, class and race, gender and class, is there before us once we begin the basic work of describing what we see reading for the inscription of a chance event that makes it an allegorical image. I have painted from this photograph over many years searching through that activity the meanings and occlusions, and in part in seeking to repair the crime it witnesses.

What crime? On 18 Feb 2020, I read a press report of a quarrel that broke out over remarks by the former premier, the last Apartheid premier of SA FW De Klerk who quibbled over the nature of the crime of Apartheid. He acknowledged that it had been a crime, and apologised profusely for his role in it, but he insisted that apartheid was responsible for relatively few deaths and that it should not be put in the same category of "genocide" or "crimes against humanity". [3]

Is crime, a crime against humanity, too big a word for Apartheid? Does this quibbling take us into calculation of degrees of criminality by numbers of the dead? De Klerk’s South African government can hardly claim, however, that there were few deaths when we have the horrifying testimony given during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or read any of the literature or study the political photography. A TRC member, Pumla Gobodo-Madikezela has written a remarkable book based on her interviews with a former police colonel who commanded a special secret unite alleged to have killed many anti-apartheid activists. Eugene de Cock was charged with crimes against humanity, six murders and sentenced to 212 years in prison. Her book, A Human Being Died That Night registers the complexities of post-apartheid South Africa and deeply explores the psyche of a white perpetrator exploring his deeds with a member of the people he tried to dominate by annihilation of those who dared to claim their own humanity. Pumla Gobodo-Madikezela’s title poses a double question. She shows that a brutal political murder indeed killed a human being but the action of this brutal inhuman killing also killed the killer as a human being.

What I see in my casual family photograph is, however, is not the evidence of brutal killing in police custody or at interrogation centres but rather the systematic infliction of social death, a psycho-social term I came across in studies of German Jewish experience during the 1930s. Social death inflicts daily psychological dying in a form of an existence unsupported by the necessary conditions of social recognition for a shred humanness. I am invoking here Hannah Arendt’s core post-totalitarian political thesis on what constitutes the human condition and what erodes it. The steadfast gaze of an African woman out of this scene of leisure —while this was the place of her work—counteracts her socio-political erasure as a person by its dignity and the presence she calls us the viewers to acknowledge. Her gaze functions as the punctum of this image. Her active curiosity serves as defiance of the obliteration of one person’s singularity (Arendt again) and a questioning of the politically-created world within she was forced to live as if a non-person, blackened, and made nameless in a servitude that never dehumanized in her actions of care for the vulnerable in her daily charge. This again invokes the ethics propounded by Adriana Cavarero in terms of the maternal as a model challenging the individualist autonomy of Western philosophical masculinized norms.

I first dared to cross the boundaries between a private family album and my professional work as an art historian in a conference presentation later published as Territories of Desire: Memories of an African Childhood dedicated to a woman whose name was not Julia. A woman I called Julia cared for me in place of her own, distant children. While my mother played golf or bridge or ran a provincial association of the Girl Guides, mourning her own unfulfilled intellectual brilliance, Julia was the physical and emotional companion of my childhood. Her given and family name disappeared for the convenience of the English tongue so I could never trace her. In my essay, I used this photograph to theorize the processes of the racialization of white children in colonial or slave-owning societies by recasting Freud’s model of sexuating Oedipalization. I reconfigured his triangle of Father/Mother/Child with the triangle of White Mother and White Father /Black Nanny/Whitened Child. In most colonial and slave-owning societies childcare is handed over to people reduced to being servants and slaves, creating often loving intimacies between the parent-deprived babies and children and children-deprived mothers of colour in domestic service. The white child learns, however, to forego primary attachments to the carer for the benefits of the privileges and freedoms the white mother and white father represent, just as Freud suggested that the sexuating of children occurs through their unconscious assimilation of the privilege of the Father over the nurturing Mother of their infancy. Thus, whiteness functions as a kind of racial phallus, as it were, and is enshrouded as a result in the confusing hatreds for the once so beloved bodies, gestures, and voices of the nurturing carers. This formation cross plaits the racializing as well as sexuating asymmetries we term racism and phallocentrism. From this I want to derive a pathosformel for this talk in which racialization and class divide women from solidarity with each other in societies disfigured by both.

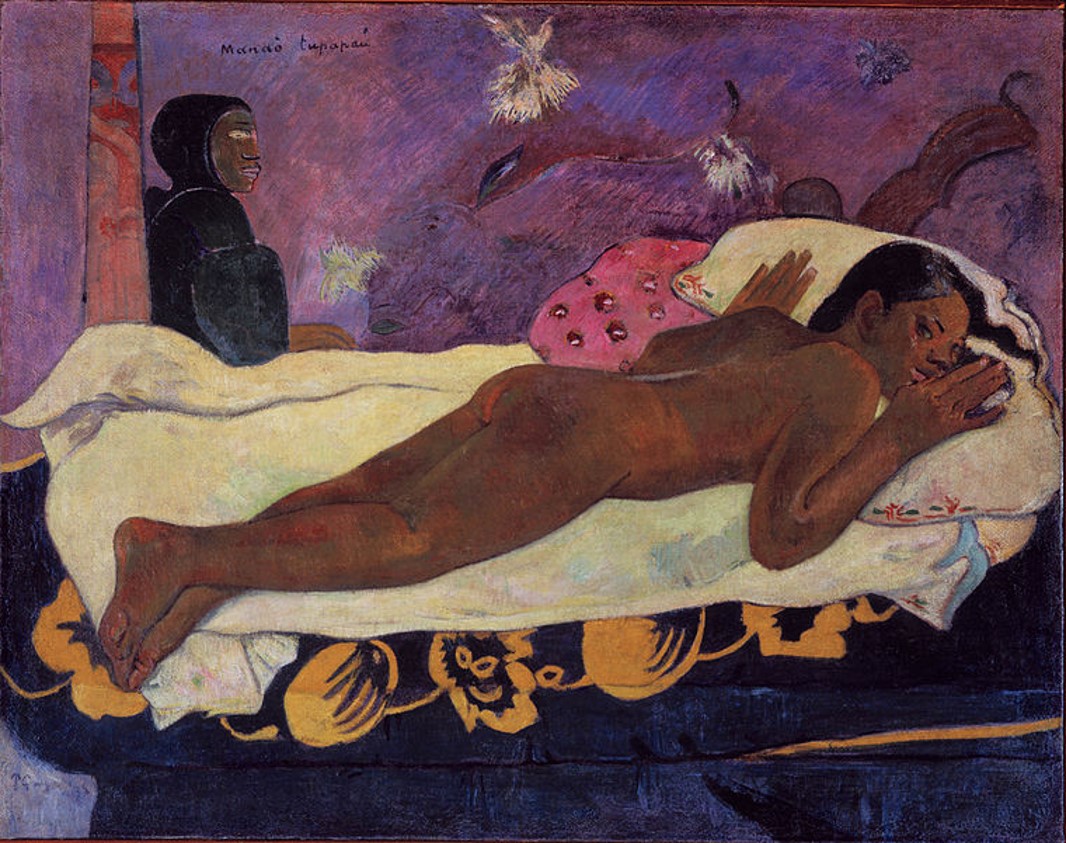

What does such knowledge imply for art history? I have had to develop analytical framework for the entangled relations of gender and the colour of art history. In a lecture given in 1993 to commemorate and honour Walter Neurath, founder of a critically important art history publishing house, I used this structure of a child and this African woman’s gaze to produce a postcolonial-feminist reading of a painting created in Tahiti by French colonial tourist, the painter, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). The painting is titled Manao-Tupapau, [The Spirit of the Dead Watching] (1982, oil on canvas, 116.05 cm × 134.62 cm; 45.6 in × 53 in., Buffalo, NY: Albright Knox Art Gallery).

In one sense, the painting repeats the pathosformula of two figures. Here the younger woman looks towards the place of the viewer/painter, the other gazes sightlessly across the space. The younger woman seems human, the other possibly an idol. Both are coded non-white by colours and non-European by features or aesthetic styling in the case of the background idol or ghost. I then create another screen in the Virtual Feminist Museum’s recasting of the Bilder Atlas on which I place the painting in conjunction with a Self-portrait by Gauguin with a reverse image of Manao Tu-papau visible behind his head, indicating the mirroring of the painting. He thus places himself as the object of the young woman’s gaze, taking on the position he records in his journals of coming home to find the terrified Teha’amana alone fearing the presence of the spirit of the dead. I add to this assemblage a page from Gauguin’s travel journals during his first stay in Tahiti, (1891-1893) Noa Noa, (only published in 1924) where we find the story and a sketch of the black naked woman’s body posed in this same, reverse direction. It was her body’s angle and the terrified expression that caught his imagination. Beside Noa Noa, I place a sheet from notebook created for his 16-year-old daughter, Cahier pour Aline. Aline never received it. Gauguin wrote revealing in the preface: À ma fille Aline, ce cahier est dédié. Notes éparses, sans suite comme les rêves, comme la vie toute faite de morceaux. Ces méditations sont un reflet de moi-même. Elle aussi est une sauvage, elle me comprendra…’ [To my daughter Aline, this notebook is dedicated. Scattered notes, without continuation like the dreams, like the life made of pieces. These meditations are a reflection of myself. She too is a savage, she will understand me.] Aline was in Denmark with her mother and Gauguin’s estranged wife, Mette Gauguin. Yet Teha’amana, the child woman in the painting, is presented as his companion/ wife, married according to Tahitian and local law. The syphilitic Gauguin had conveniently purchased a teenage virgin to cook and forage for food and to serve as his sexual servant. He painted Teha’amana in the clothes that indicate she was, in fact, as a converted Christian and no longer went bare-breasted (Merahi metua no Tehamana, 1893, Art Institute of Chicago). He also drew her clothed in 1891/2 in charcoal ( also in the Art Institute of Chicago). Yet this teenage girl entered Western modern art in a total nakedness that is as sexual as it ‘dressed’ by the artist, his colonial vision and his artistic tradition as her ‘natural’ state, even as she portrayed awaking in terror from a nightmare or vision of about the gods of the dead watching her. Why was she afraid of death so close?

What, I ask myself, would it have meant for the painter’s daughter Aline to learn of this other teenager, his father’s other wife, represented thus? What trauma would that knowledge occasion? Married abut abandoned by Gauguin when he returned to France, Teha’amana we have learned married again. She died in 1918 in the pandemic of Spanish flu that killed 25% of her island’s population. She passed on the syphilis with which Gauguin infected her to their son.

When Gauguin’s painting was exhibited his return to Paris in 1893, the critics titled the woman in the painting a ‘brown Olympia’. This colouring acknowledged Gauguin’s ploy for achieving leadership of the Parisian avant-garde in what I have termed an avant-garde gambit. Manet’s Olympia (1963-65, Paris Musée d’Orsay) had just entered the national modern art collection in Museé du Luxembourg in 1890 and thereby re-entered contemporary knowledge as the last big play in modernizing the Western tradition of the erotic nude. Avant-garde gambits comprise three moves: reference, deference and difference. Gauguin’s painting of a nude on a bed with a black attendant actively invokes—refers to—his filiation to Manet. Gauguin’s referencing also defers to Manet’s as the latest game play. But then Gauguin must invent his difference in order to take over leadership. Manet’s primary modernist reworking of the western tradition of the female nude had been effected by both prostitutionalization and proletarianization of the nude.

Manet indeed also displayed an under-age girl blatantly on for sale sexual services. At the same time, this figure defiantly gazes back at potential clients, her work assisted by a clothed Parisian working class woman of African descent. whom Manet had earlier noted as a potential model. He had painted the portrait of a woman identified in his notebooks as Laure, after discovering her working as a nanny, looking after European children in the fashionable Parisian Tuileries Gardens. In 1998, with the help of Nancy Proctor, my research assistant, we traced the birth certificate of Laure, the working woman, occasional model, and established her birth in France. Manet painted ‘Laure’ several times, once in a characterful portrait, and perhaps earlier in a painting of a scene oversees haut-bourgeois European children playing the Tuileries Gardens. Thus, in Olympia, we are looking at two proletarian Parisian women working in an economic partnership, one, the white teenager, looking back at the viewing public. Her gaze combined with her pose and nakedness shatters the conventions that allowed other paintings of erotic plays on white and black bodies to be received under the frame of being exotic images, which, following Edward Said, we have identified as belonging to orientalism —and we might add Africanism. Examples notably involve displays of nude white bodies being washed or served by half-dressed Africans.

In my view, Manet’s painting Olympia actively deconstructs orientalism by clothing the second woman in typical hand-me-down European dress bought from the second-hand markets. The doubling of the two women, their scale and ‘Laure’s’ clothing serve to de-orientalize but to class and to locate in contemporary Paris, the very genre which Manet sought to scandalize while exposing the deceits involved in contemporary prostitution and the bad faith of the erotic nude in with its19th century orientalist fantasies. Gauguin’s painting failed to recognize this critical element of Manet’s differencing, a key Derridian-inspired concept in my feminist vocabulary. Nonetheless, Gauguin’s regressive painting has taken its place in the metropolitan culture of France and in canonical art history.

My view is that Manet’s painting actually the model Laure is wearing. This is clearly a recycled bourgeois dress that working class women would buy in Parisian markets. The doubling of the two women, their equal scale and this class-marker of her ill-fitting dress serve to de-orientalize the very genre which Manet sought to scandalize and thus expose in terms of the deceipts involved in contemporary prostitution and the bad faith of the erotic nude in 19th century orientalist fantasy. Gauguin’s painting, however, failed to recognize what I would term Manet’s critical intervention, his differencing, the extended Derridian-inspired concept in my vocabulary. Gauguin’s gestureing towards differencing was an exoticization by a colonial displacement. Yet the painting was made for, and was took its place as gambit in the metropolitan culture of France and in subsequent art history.

Gauguin’s first trip to Tahiti (1891-93) was in part inspired by the novels and travel writing of a French naval officer, Louis Marie-Julien Viaud (1850)-1923) whose nom de plum was Pierre Loti. Loti had lived in Tahiti in 1872, writing his local marriage into the book Rarahu renamed Le Marriage de Loti (1880) travelled to Japan and took advantage of local marriage customs to buy himself a young wife for the duration of his stay. Both Loti’s novels, Le Marriage de Loti and Madame Chrysathème (1887) about his time stationed in Nagasaki, were eagerly read by Gauguin and by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) whose personal interpretation of the fantasy of an oriental virgin wife is, however, clothed and modelled by a thirteen-year-old Arlesienne, the painting being titled La Mousmé (1888), a name for such brides he found in Loti’s novel.

Novelists and librettists were also intrigued by such tales, including Loti’s has delivered to us, indirectly, one of the classic works of the operatic canon, Madama Butterfly (Giacomo Puccini, 1904). Like so many operas, the opera will kill its heroine. As listeners and viewers of the three-act tragedy, we will be drawn over time to her tragic end, suicide, being compensated by gorgeous—or cheaply emotional—music, to which I have to confess I am terribly susceptible. I cry at the end of both Verdi and Puccini. My question, in a research project exploring the issue of Performing Violence what does opera do to and with us in this context of colonial Orientalism? Do we remain merely spectators at a culturally canonised pageant of gendered killing which we consume tearfully as aesthetic experience? As an multi-sensory and multi-mode aesthetic experience combining creative embodied skill and artistry and performance, voice and above all, duration, can opera make us more than spectators? Are we not forced by its prolonged use of singing and music to become witnesses to the violence the plot engenders but also to the pathos of another entanglement of race, class and gender against which we are ethically called to revolt?

At this point in the recorded lecture, I screened a 5-minute clip from the final scenes of a production of Royal Opera House, London in 2018 with Ermonela Jaho as Cio-Cio-San. The scene brings us face to face with Cio-Cio-San as she prepares to commit die with honour rather than to live with dishonour. The viewer is thus centred, focalized in literary theory, with the subjectivity and assumed agency of the woman, otherwise powerless before the racism of her encounter with the American naval lieutenant. As she is about to plunge the knife into herself, her blonde child runs in. Hiding the knife and full of grief, Cio-Cio-San sings an aria apologising to the child that she has to abandon him to the white mother. Being exposed to the musical translation and duration of this grief and horror as well as the singer’s physical and vocal performance makes us how the musical dimension aesthetically reformulates as pathos the plot, while creating a score for the maternal grief of the silent African woman on the beach and in the photo with which I started.

Let me be clear. I am not condemning wholesale these artists or writers and their works as crudely sexist, racist, colonial. The naming of such ideological orientations enacted and formulated in their work is an ethical obligation and must be teased out in complex relations of image cultures and social histories, aesthetic practices and new sensitivities. Yet, as I learnt from a key influence on my development as a social historian of art, T J Clark argued, all artworks have ideology as their materials. Each painting or opera, however, works that material in ways that require close reading for possible internal deconstructions of the normalization of ideological formulations. Thus, the manner of Manet’s rendering of the undernourished street kid, striking her empty but compelling pose as she frankly sells her body on the commodity market of sex and money, made the topic unassimilable to its male public, who could not bear to see what that look demanded they see in/as themselves. Placing this painting in the Salon with its mixed gender publics, Manet also obliged the bourgeois wives and daughters to confront what convention and their Catholic girlhoods kept them from knowingly knowing, they had to be in the same space, these two spaces of modernity riven by cross-class, cross-gender sexual exploitation of the bodies of vulnerable women.

In operatic form, Puccini’s pathos leaves us emotionally ravaged as we leave the theatre, uncomfortably haunted by the child who tells Pinkerton in Act 1 that she is only 15, when she is first ‘purchased’ in the delusion of being married for love instead of temporary usage, and who dies by her own hand a mother, now aged 18 in a form of an honour killing traditionally reserved for men. Abandoned and then forced to yield her child to the white mother, her Japanese body, her love, her motherhood, held no currency sufficient to counter the colonial and the racist terms of the American empire. Do we come away from the opera thrilled by the opera singer’s virtuosity but blinded to the crude child abuse that has been on stage for several hours that we might, in our own culture, condemn.

From deep in the colonial era and its racialized sexual politics, their inscription and even oblique contestation in modernist painting, I want to leap to a contemporary painter of African birth and also British descent, Lubaina Himid (b. Zanzibar in1954) who has to renegotiate the double heritage of the racializing and patriarchal colonial and its canonisation as the Western art and artworld in which she practises. I now ant to introduce amonumental painting on hanging cloth surrounded with cut outs titled Freedom and Change Lubaina Himid from 1983. Freedom and Change was created at the point at which a Black Women’s Art Movement in Britain was challenging the inattention to and invisibility of black women artists. Through the curatorial and research energies led by Lubaina Himid the works of Ingrid Pollard, Claudette Johnson, Sonia Boyce, Veronica Ryan, Marlene Smith and Sutapa Biswas were exhibited. With Freedom and Change, we return to a beach that stands for the shores of an imagined African continent whose coasts have served as the dark ports from which the millions of Africans were deported into enslavement via the horrific middle passage or across the Indian Ocean to the subcontinent. The beach can also evoke the Caribbean Island nations, or even the coasts of British Isles and Europe, sites of invasion, emigration, and immigration. The coast and beach are signifiers of the colonial.

Lubaina’s Himid’s work employs many media including painting, collage, textiles, and cut-outs. The scene she creates in Freedom and Change is dominated by the joyous, dancing bodies of two clothed black women, running freely along a beach the experience in ‘freedom.’ Any beach can carry a childhood memory or evoke a lost home, a forced exile, economic migration or enslavement. These women, however, possess their beach. As they run, we see in behind and beneath their feet heads of white men, now buried up to their necks in the sand. The hand of one running woman holds the leashes of the ‘dogs of war’ that they might at any moment let loose. Their bodies are clothed in collage that evokes the rich colours of African and Indian fabrics that Lubaina Himid would develop as a visual language throughout her work blending voice and textile in conjunctions that treasure the varied aesthetics systems of the African continent. The two women dance their claim for freedom. From what?

The painting is also a speaking back to modernist art’s appropriation of the aesthetic traditions of the African continent. This painting performs an art historical conversation and a erbuke. This artist is not playing the avant-garde game of reference, deference and difference. There is instead reference to and defiance of, European appropriation of the African or Polynesian other for their modernizing visual vocabularies. In particular, Himid speaks back to Malaga-born Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), whose work Two Women Running on the Beach (1922, Malagá (coastal port) Museo Picasso) is typical or Picasso’s post-war return to classicism still tinged with his archaicism and Africanism. His monumentalization of the female subject is canonised in his portrait of the greatest Cubist of them all, the Jewish lesbian intellectual, writer and modern art collector Gertrude Stein (1874-1946; 1905-06, New York Metropolitan Museum), a portrait that demanded between 80+90 sittings as the young Spaniard struggled to find a form adequate to the brilliant thinker who understood his artistic struggle to emerge from the nineteenth century and be the artist she considered grasped what needed to grasp the reality of twentieth century. Her study Picasso (1938) is the most profound analysis. Picasso conferred on her physical monumentality but fell back on mask-like features derived from the archaic Iberian sculptures which he then borrowed for his Self Portrait with Palette (1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art). Picasso’s searching beyond the European art canon for modern formulations of body and features also precipitated his gambit to contest both the Manet-Gauguin avant-garde game and the exoticizing orientalist painters. In the summer of 1907, Picasso modernized erotic orientalism, colonial sexploitation and also invoked de-orientalising modernism in his own monumental reconfiguration of Manet’s prostitutional nude and maidservant, Olympia. Hailed for its formal derangement of the canon, the massive Demoiselles d’Avignon (New York: Museum of Modern Art) has also been interpreted as the artist’s anguished confrontation with both an intensity of sexual desire and dread fear of death in an era before penicillin tamed the death-dealing threat of syphilis.

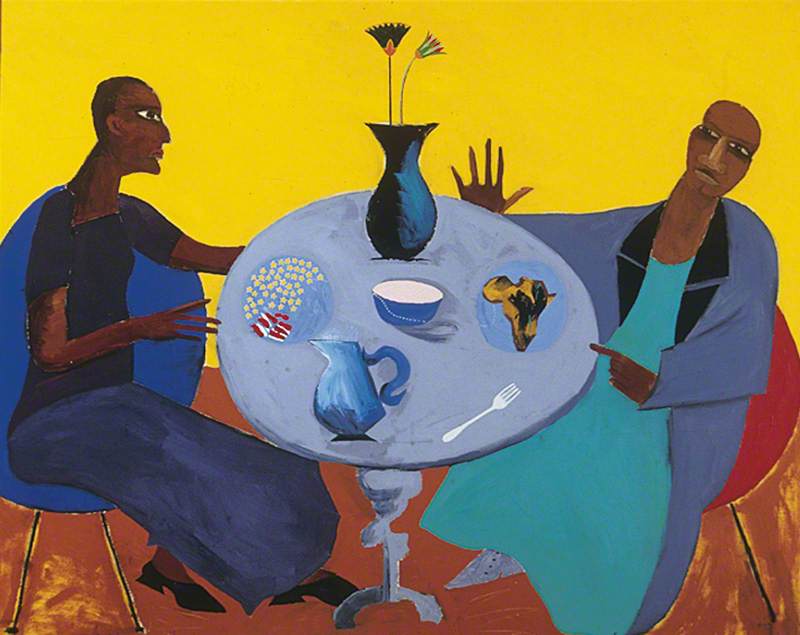

The lesbian intellectual and modernist poet of the erotic, Gertrude Stein creates, for my exploration of the topos of two women, another lineage. She becomes a link back to Lubaina Himid’s jubilant reworking of the trope of two women that I have been tracking. Himid takes the two women back home to the dinner table where two lovers discuss the fate of the world and the histories they have been delivered. In this series intriguingly and tragically titled Revenge, first exhibited in 1992 comprising four large paintings and ten smaller studies towards a monument to a tragedy on the ship, Zong, carrying enslaved African who cast into the sea to drown, Lubaina Himid placed two black women engaged in heated debate about what to do in so dangerously vicious a world and an artworld of images which did not confer intellectual, political and historical agency upon the black woman as image.

In Five two women sit at their table and rethink the legacies of an Africa made into the carcass of a ‘dark continent’. They plot the destruction of the European-American hegemony. In Between the Two My Heart is Balanced, they reject existing maps and renavigate the Atlantic as the un-mourned burial grounds of African men and women. In a third Act One, No Maps, they sit in a box at the theatre, remembering some Parisian conversations with Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt for instance, or even Laure the model and nursemaid, or even Jeanne Duval, the companion of Baudelaire, wondering what can be done with what this dismal culture offers to them to see.

Five is both a history painting and a conversation. Maud Sulter, Ghanaian Scottish poet and artist is portrayed on the left, her 1920s modernist style of dress evoking for me another Black artist, the African-American Josephine Baker (1906-1975), a brilliant and de-colonizing dancer, a cabaret owner, a glamourous singer, and a decorated resistance fighter during the Second World War. As a Civil rights activist, she challenged US-American segregation that constantly humiliated her even when she had become a major celebrity, refusing to sing to segregated audiences even as hotels required her to enter through the kitchens. She also became the adoptive mother of 2 daughters and 10 who formed the ‘Rainbow Tribe’. The children came from many regions, peoples and ethnicities whom she raised them together in familial love.

On the other side of the table is a self-portrait of Lubaina Himid herself, who, however, also invokes anther queer figure of the early 20th century. She is wearing the coat of Gertrude Stein, a sartorial link opening a rabbit hole down which I can slide to arrive at an apartment full of ‘modernist paintings, Cézannes, Matisses and Picassos, at 4, Rue Fleurus in Montparnasse, Paris, the home Stein shared with her life partner Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967). In 1923, the American artist Man Ray (1890-1976) photographed the couple with Stein’s collection on the walls in a home that was, in effect, the first museum of Parisian modern art. If cosy marital domesticity amidst challenging art is the scenario May Ray creates, the brilliant queer photographer Cecil Beaton (190-1980) more radically explored the politics of the queer image in 1937 when he posed the two women in his studio in a variety of arrangements of ‘twoness’. The image that I chose for a chapter on Himid’s Revenge paintings in ‘Differencing the Canon (1999) was one that simply place the lovers face to face, equally positioned in space and without hierarchy.

We will leave Lubaina Himid and the women of Rue Fleurus to their discussions to return to the beach on the string of Lubaina Himid’s own natal memory work. Natal is the adjective associated with being born. Natal, pronounced Nataal, is Portuguese for Christmas, and the name was given to the landing point in the South-East Coast of Africa where the Portugese traveller, Vasco da Gama (1460s-1524) stepped ashore. I invented the concept of natal memory to define memory the deepest, perhaps unconscious but accumulating impact on our psyches and hence our memories of our earliest sensations of place, space, colour, sound and smell that marks us forever, especially if we live in exile from the places of our birth.

Lubaina Himid was born on the Island of Zanzibar but left it as a baby after the tragically sudden death of her young father from malaria. Her English mother returned to England to continue her work as a designer. She raised Lubaina with her German-Jewish refugee second husband, who introduced Lubaina to opera. In a soon-to-be-printed conversation about her art and opera, the artist recently explained to me that she had learned to love the artform for two reasons. Throughout these anguished tales of love, deceit, betrayal and destruction that entertained the European courts, aristocracy and bourgeoisie for four centuries of colonization and empire, opera composers and librettists wrote conversations for women. Firstly, women’s voices entwine and separate in glorious displays of vocal and artistic brilliance in long sequences, be that in Norma or Maria Stuarda. Secondly, these conversations take place these women individually or together seek to work out what to do. The voices musically explore the struggle to understand their fates and decide how to act in ways that form a momentary but profound counterweight to the often deadly end the plot has prepared for them. Catherine Clément calls ‘Opera: the Undoing of Women’(1979) because its stories so often end with a dead woman. Lubaina Himid derives from opera these moments of women singing to and with each other or alone, moments of intense subjectivity being staged for the listener-viewer. This is a profound analysis and insight into the ways even the most depressingly racist and sexist narratives can aesthetically, if briefly, create for different members of the audience, moments of reparative access to women as agents within worlds defined by powers they cannot yet defeat.

Born in Africa with her own natal memory, Lubaina Himid constantly returns to the sea as the space of home memories but also as the historical space of memorializing the trauma and historic ruptures created by enslavement. Her series of seven paintings Beach House (1995) create lonely structures ranging from subdued to often intense their coloration. At once ghostly architectural forms, set in dramatic locations of night and storm, dawn and darkness, they perch on the edge, on rickety legs, like silent monitors, watchtowers, creatures with evocative titles, Tuesday, Weave, Mars, Cake, Grate, Metal/ Paper. Only as an adult did she return to Zanzibar itself. In 1999 she painted an almost abstract series titled Zanzibar, writing in the catalogue:

The fourth journey was the painting of the series itself, an exercise in speed, daring, calm and panic. I listened to a great deal of music—a combination of whatever Radio 3 had to offer and a careful selection of CDs, mostly women singing, trying to remember and to soothe. There are paintings of cloves, of rain, of closed shutters; there are paintings of the sea, fishing nets, death from malaria and, of course, women’s tears.

This memory work and journey brings us back to Africa, a locus of premature parental loss, death and mourning, elements that I already intimated infuse my own photograph and biography. Is autobiography permitted in our scholarly work? In 1988 Donna Haraway explained how all knowledge is ‘situated’, while. A ‘personal turn’ in feminist thought was traced by Nancy K. Miller in her text Getting Personal: Feminist Occasions and Other Autobiographical Acts (1991).

I first dared to move between theory, history and the personal in performance-presentation at a conference celebrating the publication of cultural analyst Elisabeth Bronfen’s book: Over Her Dead Bod: death, femininity and the aesthetic. Bronfen is one of our most brilliant literary, film and cultural theorists who is incidentally also a trained opera singer. I once invited her to Leeds to give a lecture and seminar, before which I also requested that she sing. The students were astonished as from the lectern, she delivered some of Berlioz’s Nuits d’été with the power of the trained voice that always surprises. My experiment with this novel form of hybrid theory and situated narrative, family and history was in seven sections, like the Jewish menorah, the seven branched candlestick that signifies the asymmetry of the six days of creation and the seventh day of rest. Titled Deadly Tales, there were seven narratives about death and the unending character of mourning that I later made as a film and, on several occasions of its projection in exhibitions, I delivered it as a live performance. It is also became a published text, subtitled Portrait of a Feminist Intellectual Obsessed with Death.

It was the least academic lecture I have ever given and was written in a single writing session. sitting. It came to me as a kind of artwork. The seven sections tracked from an art historical lecture on a 16th century painting about the death of a woman in childbirth that represented the concepts of the social versus the private body to the now famous and memorialised death of theorist Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) in September 1940, juxtaposing this public end of a thinker’s work to the privately mourned death of my exiled father-in-law who was the sole survivor of his immediate family. An elderly couple, his parents had been murdered in Auschwitz in December 1943.

The three final branches of the piece were more theoretical: a discussion of Roland Barthes ‘s celebratedly personal mourning memoir Camera Lucida, in which his mother became a figure on our theoretical world, even as a mythic image of her as a child was withheld by Barthes while he built his thesis about death being the real meaning of photography. Puzzling why Barthes’ mother’s death could acquire cultural even theoretical status, while mine would be dismissed as being a personal matter, the penultimate section was a theoretical critique of Freud’s psychoanalytical theories of sexual difference from which the mother is absented, ignoring and inadequately theorizing the significance of the maternal for the formation of feminine, and indeed masculine subjectivities. The final section was my reading from Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead of a section denouncing playacting death in art or theatre in the face of the unrelenting reality of death as ‘the endless time of never coming back’ for those who are bereaved. This linked back to the dark core, section four, of the seven, that was a personal testimony to repeated pregnancy loss and the trauma of childhood maternal bereavement that such losses aggravated as I sought to become a mother. The aim was to play a real pathos, spoken and performed across a different kind of Bilder Atlas of death, dying and mourning in the 20th century, working to create and fill with my own voice and memories the empty space of the feminine and embodiment amidst the great men thinkers.

The slogan of ca. 1968 feminism has always been that the personal is political. In the current age of what I call (pace Derrida and Spivak) insta-grammar, the instagrammification of affect as sentimentality, the personal has ceased to be political; it replaces the political. What feminist politics and theory sought to declare, even as we could not comprehend its significance yet, was the intricate web that bound our bodies and imaginations, our psyches and our words, our actions and our overdetermined socio-economic conditions for action to the domains of power and necessitated political analysis for resistance and transformation at every level. Life and death, birth and loss are shared events in the human condition. But how we experience them and how they are or are not acknowledged is differential in ways that are political. These are also situated, social, and historical.

In this final turn, I make my way back to the beach, this time in Cape Town where I shall find a conversation between three women after the end of Apartheid. To get to them I need a final turn through the island that will be in their purview as two Black and one white Jewish South African take possession of a hitherto whites only space in Kaapstaat, the port that so many Europeans from the Dutch to the French to the British sought to control for their colonial voyaging to India and the East. Any one on that beach we will be looking out onto Robben Island, a prison island that will take me back to Apartheid and its crimes, the frame of my own natal memory, the home into which I had no right to be born.

I want to introduce the works of Santu Mofekeng, a brilliant South African photographer, born in 1956 in Soweto, who tragically died on 26 January 2020. Famous for collecting photographs of the considerable Black Middle Class who were dispossessed of their property by the British colonial powers in the early 20th century, Mofekeng later specialized in landscapes which I first encountered in his publication and related exhibitions, Chasing Shadows 1997. One set of images transfixed me.

When I first glanced at this photograph, I imagined I was looking into cell on Robben Island, the notorious prison in which so many of the freedom fighters of the ANC were imprisoned during the Apartheid years and forced to do backbreaking labour in its quarries. Why did I think this? Because I knew the photographer to be South African: Santu Mofokeng. Was I making limiting assumptions about the photographer because he was a South African? Was I expecting an inevitable reference to the history of political oppression in his country? Probably.

Then I read the caption. The scene before me was, in fact, a torture cell in the Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, north of Berlin, Germany, built in 1938 by the SS— indeed it was owned personally by Heinrich Himmler who leased back to the National Socialist state in return for an allowance for each prisoner from which he made a tidy profit by skimping on what he gave them. It opened in May 1939. The majority of its 132,000 inmates over the next six years were Polish, Soviet and German women, with a smaller contingent of French. Jewish women formed a 20% minority and a tiny number of Jehovah’s Witnesses were incarcerated there. 117,000 prisoners died under the atrocious regime of slave labour, brutality, torture, experimentation and starvation.

When I began to study Santu Mofokeng’s Landscapes of Trauma, I was already studying Ravensbrück through the memoirs of former inmates Germaine Tillion, Genevieve de Gaulle, Charlotte Delbo, as part of a current research project titled Concentrationary Memories: The Politics of Representation. This project controversially seeks to make a tactical, theoretical and historical distinction between the exterminatory sites and processes of racially targeted genocide that are widely commemorated as the Holocaust or Shoah (and by the Roma as Porajmos), and what the French Trotskyist political deportee, David Rousset named on his return to France in 1945 from Buchenwald: ‘l’univers concentrationnaire’.

In his book analyzing the camp as system, Rousset offered a political anatomy of the perverted ‘order of terror’ (Sofsky), experimentally created by the SS under the Third Reich in the huge network of concentration camps that were initiated in 1933 to dispose of political opponents of the fascist regime. By 1945, there were over 10,000 camps all over the Reich and its satellite countries with a final population of over 750,000. Rousset also argued that the camps (which were highly visible near towns and villages) were the central instruments of state terrorism, whose effects were additionally to politically eviscerate the German nation itself.

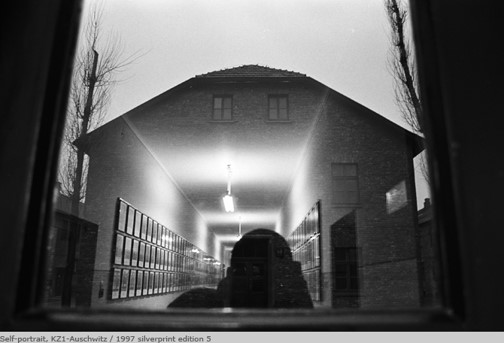

In contrast to this visible system of camps, the industrialized extermination of two racially targeted European minorities, the Jews and the Roma, took place more or less invisibly in only four special camps, hidden in remote parts of Poland. Created in 1942, they were dismantled or obscured by mid-1943. The exception is the complex known collectively as Auschwitz, to which was added a second camp at Birkenau in 1942. Auschwitz II-Birkenau became both a dedicated killing centre with four gas chambers and crematoria and a concentration/slave-labour camp for those selected for prolonged exploitation and certain death. As much evidence of genocide as could be destroyed was, however, blown up or burnt down before the arrival of the Red Army in January 1945, leaving Birkenau a desolate ruin. Auschwitz I, the original camp was itself a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners and Soviet prisoners of war. It is this former military garrison hamlet that is the memorial site and museum space most people visit, confusing the two if here overlapping systems of concentration and extermination. Santu Mokokeng visited and photographed both sites.

Concentrationary Memories project aims to draw out the political implications of a specific kind of memory. If Holocaust memory is about mourning an exceptional event and a unique human catastrophe in the past, concentrationary memory, created by writers such as Rousset and taken up by the filmmaker Alain Resnais in Nuit et Brouillard, is of a different order. Concentrationary Memory is anxious. It seeks to undo the frontier between past and present and politically to use memory of the concentrationary universe to agitate the present into perpetual vigilance about any new instance of totalitarianism and its terror: Algeria, Soviet Union, Argentina. It believes that the Nazi and Stalinist regimes introduced a terrifying novelty into the world in which, as Rousset argues, ‘everything is possible’. This understanding is taken up by Hannah Arendt, in her Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951, where she too seeks to make us confront ‘the shock of experience’. (Preface, viii 1968).

So, what does it mean that a Black South African photographer casts his gaze upon the trauma landscapes of Germany and Poland that are the overlapping sites of the concentrationary universe and of exterminatory racism? What is the effect of his re-visioning of these now iconic sites of Europe through his meditative eye and reflective aesthetic sensibility? What does he see? What does seeing with him show to us? Photographed in a sequence titled Landscapes of Trauma (1997), over-known places are profoundly transformed by Mofokeng’s by what and how he chose to photograph as he journeyed across Europe. He is a solitary viewer/visitor to empty, distilled, chilling places. The sequence discloses relations between torture and bureaucracy; modes of transport with deadly destinations share the train lines with contemporary tourists visiting and staying in hotels overlooking railway termini so close to one that delivered millions to pain and death. Like Bracha Ettinger an Israeli who senses the terrible death beneath the grass of Europe’s soil or in its waterways, Mofokeng disturbs the beauty of a sylvan scene or river with a caption reminding us of the dispersal of the murdered people’s ashes.

What does it mean for a South African photographer not merely to look at but to have travelled to and placed himself in these landscapes of trauma when for a period of almost forty-five years his own country was effectively turned into one vast concentrationary universe for its African population, complete with its constant state of exception, its torture chambers and prisons that were death houses, with its brutal and sadistic secret police allowed to perform a racially targeted genocide that, in the country as a whole was both spiritual and material through systematic impoverishment, forced dangerous labour, emotional emiseration, cultural deprivation, educational exclusion or alienation, human degradation and indignity. Is his gaze one of recognition of the European origins and modelling of the Nationalist policy? Or is it human compassion arising out of known suffering? Are these images displacements onto historic scenes and another place of violences and suffering too well known and perhaps almost unbearable to have resonance because they have become the media currency of a one-dimensional vision of South Africa’s dreadful past? Or are they a brilliant photographer’s contemplative envisioning of the sites of a dreadful moment of twentieth century history that was a human catastrophe all can and must mourn that might also lead to understanding of an African concentrationary universe still carried ‘in the muscles’ –Rousset’s phrase?

In the final image of the series, there is a photograph titled Self-portrait KZ1-Auschwitz. Photographing, through a window, the barrack outside the gallery in which the photographer stands, the surface of the windowpane catches the reflection of the illuminated interior with its gridded documentary display and harsh fluorescent light. This reflected interior is projected onto and opens up the brick building beyond. Against the back illumination of this reflected interior, the photographer becomes a dark silhouette. We discern a shoulder, a head, the edge of the camera and its supporting arm. The lighting as well as the use of black and white film turns this silhouette black. Not only does this locate the photographer in /at Auschwitz KZ1: the Stammlager whose two storey-brick buildings have been made into museum spaces that are much visited. The photograph makes him a stain in this picture, marking this commemorated history with his presence as a photographer at once anonymous and an African presence rendered ‘black’ within the racist regime: now indirectly belonging to this landscape of shared trauma.

From Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen to Auschwitz in Poland to Terezin in the Czech Republic, this South African photographer travelled in 1997 uniquely endowing these iconic landscapes of trauma with a spiritual intensity that deflects their usual function as images of atrocity into a meditative register of respectful mourning. Could this be a form of concentrationary memory, not only agitating and vigilant, but also tearful? Totalitarian terror was not confined here, and not destroyed along with the barracks of Birkenau. There all should have learnt to stamp it out if ever any aspect of its vile inhumanity rose again. Six years or even fewer are commemorated as the decisive catastrophe of Europe’s twentieth century. The African peoples of South Africa endured forty-five years of a concentrationary universe.

Concentrationary Memory seeks to shift the focus from the uniqueness of the Shoah and to allow, through the transit between instances of the concentrationary universe, a relay of memory and reciprocal acknowledgement of the violation of humanity. It draws on Hannah Arendt whose Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) functions as a key theoretical text. Two elements of that majestic book are significant. The architecture of her study of totalitarianism is tripartite indicating a historical conjunction that gave rise to its terrifying novelty: anti-Semitism, Imperialism and Totalitarianism. She was one of the first political theorists to recognize that what the Nazis did in Europe was premised on Imperialism and in effect brought home to Europe many of deeply racist policies and colonial imaginaries fostered in the imperial project across the globe to which peoples of Africa and the Subcontinent had been the experimental victims. One of her most unforgettable and challenging chapters is, in fact, about South Africa and the formation of Boer/Afrikaner mentality in its period of enslaving Africans whom the Boers remodelled in their own dislocated image. But the conclusion of the book is what relates to our topic here tonight. Arendt argues that the lesson of the horrors of imperialist totalitarianisms that became genocidal is that the fundamental character of humanity that Nazism strove experimentally to destroy is its plurality.

With Santu Mofekeng’s direct imprinting of his post-apartheid creative self on this other site of the abolition of the human condition that was Apartheid, I asked myself if we should consider Apartheid South Africa itself as a concentrationary universe. So I go back to beach to a conversation recorded in a film Welcome to the Human Race by Betty Wolpert with two women who struggled against and suffered under Apartheid, Ellen Kuswayo and Joyce Seroke. I want to give voice to the Black woman on the beach that is iconized as a memory I do not own in the photograph from the Family album. I will let them have the last word. Before I do so. I hope what I have demonstrated that being one element of the creation of a feminist history of art involved the dissolution of that term itself, the challenge to the discourses that constitute art history as a discipline in order that the obligations my many prefixes place upon me can be enacted through new conceptualizations of the entanglements of race, classe, gender, sexuality and empire while these are also the threads from which our cultural forms are woven. We must learn to read across them, discerning their patterns and the uneven attempts these artworks make to oblige us to look at and see them. Sometimes we have to look with the other and not at the other.

All knowledge situated, grounded, historical. All thought is difficult. Art is both. Art is both. I remain defiantly committed to the difficulty of thought and of art. I challenge Adorno’s maxim that art will inevitably be betrayed by commodity culture. Art indeed runs terrible risks of aestheticization of the real violence of a human world but, as Adorno compellingly admitted, it may be only in art, difficult and challenging, that some brief moments of an encounter with that real are possible despite the commodified and financialized and pacified forms in which art comes to us. My work has been the long struggle to articulate art, thought and difficulty. The obligations to see and know the hurts of the world continues. To learn from the artists who dare to show them and discern critically the art that deceives us is a critical project involving feminist, social, international, queer and postcolonial antennae.

Thank you for your attention.

Griselda Pollock

Professor, University of Leeds; 2020 Holberg Laureate

7 June, 2021

Footnotes

[1] Jo Spence, Beyond the Family Album, photographic installation, 1979; exhibited at Three Perspectives on Photography, Hayward Gallery, London, 1979. See http://www.jospence.org/work_index.html; Roland. Barthes, Camera Obscura: Reflections on Photography [Le Chambre Claire, 1980]. Trans. Richard Howard. (London: Fontana, 1981).

[2] Julia Hirsch, Family Photographs: Content, Meaning and Effect. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 12.