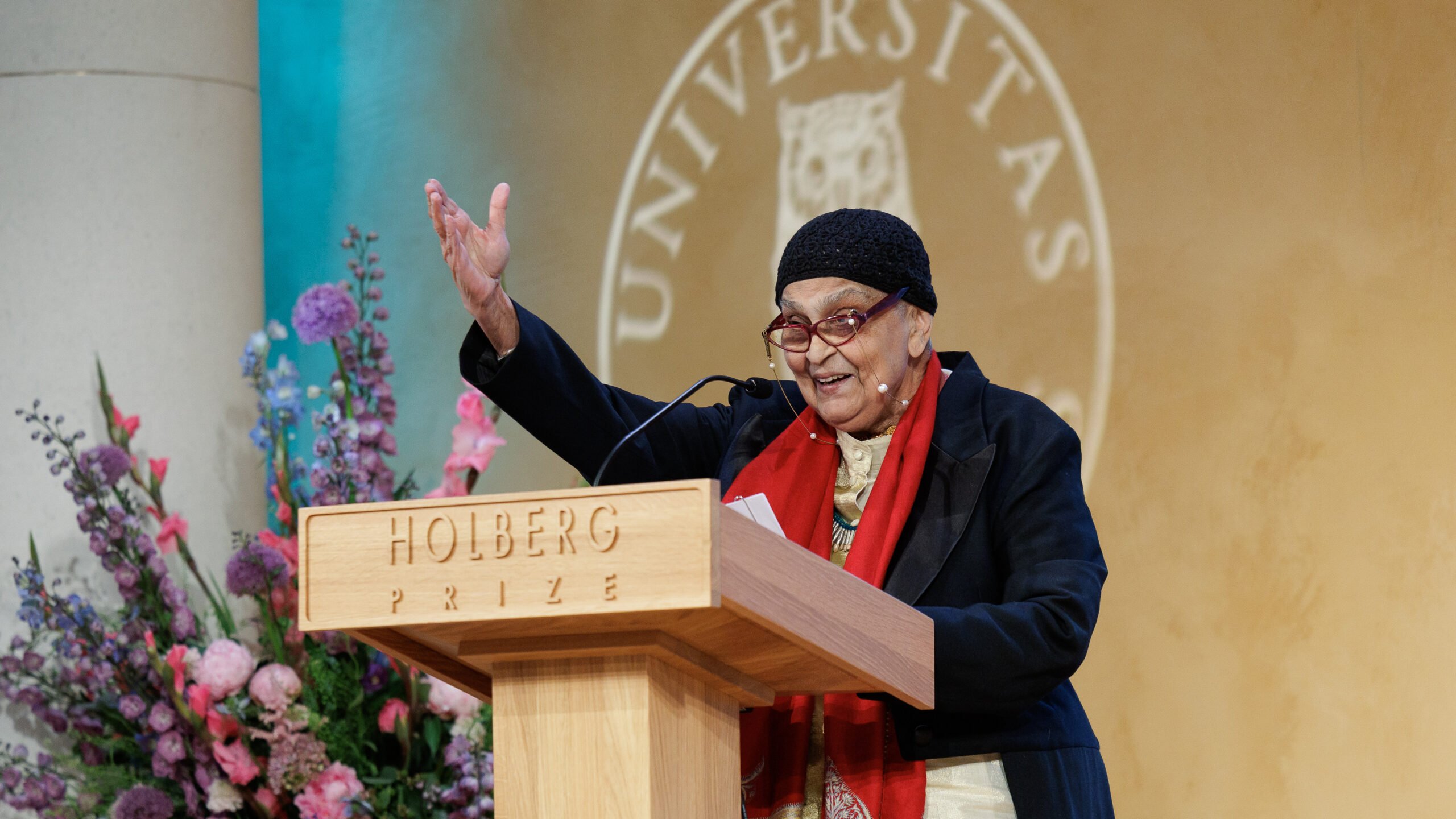

The Holberg Prize was conferred upon Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak on 5th June. Her acceptance speech is published here in full.

Thank You

In 1957, 10 years after Indian Independence, a group of us adolescents took an oath not to use pre-democratic honorifics such as Majesty, Highness, Excellency, etc. Apart from me, only one other of that group, the film critic and activist intellectual Samik Bandyopadhyay, is still alive. So, here I go: Dear Crown Prince Haakon, Minister of Research and Higher Education Sigrun Aasland, Madam Rector Margareth Hagen, Nils Klim Prize Laureate Daniela Alaattinoğlu, esteemed members of the Holberg Committee and the Holberg Board, friends and colleagues! I accept the 2025 Holberg Prize with shock, surprise, humility, and bliss. Thank you. Bruno Latour, Ian Hacking, Natalie Zeemon Davis and Fredric Jameson, the most recent deaths, are with me.

I accept this significant prize in the name of peace, in Palestine, in Ukraine, for the Rohingyas, for our battered world.

And it is my responsibility to mention here prizes of another kind, as follows: for the last forty years, I have run elementary schools in “backward” areas of my home state of Bengal. At first I don’t give houses. My teachers have to create interest in the locals and build themselves a shed. And then, if the school has run regularly, like a school, for two or three years, I build them a real school. In 2011, I told the villagers at Haripur village that their school would now get a building. I was planning to buy a bit of land in the area. When I arrived in the village, I was presented with a badly printed legal document in Bengali, signed by the thumbprints of four local landless illiterate sharecropping brothers, giving me and my white British assistant the bit of land between their four adobe huts for building a two-room school. Never in history has a so-called Untouchable donated land to a caste-Hindu and a white man and never since then. I kept myself from giving way to tears, telling myself with gritted teeth that I had to act as if this was perfectly normal.

This is a prize that I cherish in another way from a grand prize such as the Holberg. Indeed, from then on, it was as if the donation of land from subaltern to elite for the building of schools was the rule for this social group, certainly not required by me.

The second time, the documents will show that nearly 30 technically landless sharecroppers came forward with tiny bits of land that, put together, made enough space for a two-room school. The smallest bit of land was so tiny that it did not register on the government’s computer!

And now, at my newest schools, an extremely poor person was slapping mud on wattle to build a small dwelling, for me to sleep in; when asked why he was doing this, when he had only talked to me for half an hour or so. “She has touched me inside,” said he.

These are my prizes, of another kind, nameless but powerful proof that I must be doing something right.

In New York City, I return empty plastic soda bottles to big machines for 5¢ back on each, in order to hang out with subalterns from many ethnicities, female, male and trans, without seeming engaged in top down philanthropy. They help me manipulate those awkward redeeming machines, as they help each other. One such guy, an African-American with a feather in his do-rag, helped me, gave me 60¢, and walked away. I pursued him into the street, for I didn’t think the money was mine. “People give me money,” he said, “so I thought I would give you some.”

Enough. I thought this audience would sense that these prizes, since they would never get on digitized publicity, should be mentioned even as we are celebrating the worldwide one!

Bjørn Enge Bertelsen told me I should say something about my current work. Let me speak, then, of my slow pursuit of contingency over the decades. Let me tell you another story. In 2020, I was teaching a course with a celebrated mathematics professor at Columbia University. He invited an equally celebrated mathematician, Kevin Buzzard, to teach our class one day. He seemed at that point to be interested in numbers theory. And so, at the end, I asked him why he was interested in numbers theory, and he said “Because I can get correct answers.” And I said, “but that way you miss the contingent.” He seemed to like my comment but we did not have the time to take it any further.

Over these last few days, it has become abundantly clear to my audiences that, as a humanities teacher, I am focused on the contingent that is unaccountably generated by every seemingly necessary system. The contingent escapes every system, however complex. This can be fully suffered when you are working the system. In this brief compass, all that can be said is that this contingent (a wild contradiction, the accidental) questions and supplements all totalities. It is unverifiable in terms of the system we have been developing, and is the prime mover of history. Without this moment, available to the imaginative activism of the humanities, we see totalitarianisms committed to preserving the system at all costs, all over the world – regardless of left and right.

Three of us friends read a bit of Hegel some Sundays. A couple of weeks before I was obliged to write this down for you, we read in the Foreword to Hegel’s Phenomenology, that the accidental as such shows us the greatest work of the negative. Then the next week we read that it is the accidental (I am obliged to read “contingent”) that changes shape (since it must remain accidental and moves from the human subject’s apparent control into the abstraction of the worldly) to show that in that abstraction the positive and the negative are the same substance because it shows the uniformity of the capacity to differentiate. To insist that my system is necessarily true is to insist on totality and may lead to totalitarianisms mild or harsh. To leave the space open for what has not been anticipated and what cannot be predicted on the basis of any prior calculation to emerge is to acknowledge the possibility of change, of active historiography as relay. We will then work for the philosophers of the future rather than close our perfected systems.

I study the great twentieth-century visionary historian and sociologist W. E. B Du Bois. Let me quote here his acknowledgement of contingency: “what I have done well will live long and justify my life: . . . what I have done ill or never finished can now be handed on to others for endless days to be finished, perhaps better than I could have done. And that peace will be my applause.” “Handed on to others for endless days to be finished;” this narrativization of contingency can be called the future anterior that crowns good practice – that something else will have happened from what we must so tightly plan; and it is of course the unverifiable telos of all events of life, act, or thought; the unverifiable: fiction as goal – and it is the humanities that teach us to learn from the unverifiable, the singular, thus giving us a special focus on the knowledge produced by the qualitative social sciences.

Think of Karl Marx insisting that the proletarian revolution of the nineteenth century will take its content from the poetry of the future. Marx, a Ph D in European classical jurisprudence; hard to understand in this simple declaration unless involved in working the system. I am not trained to argue this into probability in the natural sciences.

Another thought I have been repeating these last few days has been that, if all other disciplines produce knowledge, the humanities – literary and philosophical – teach the practice of learning. (A systemic suggestion that gets undone in the doing.) To know something is to make it the knowing subject’s object. To learn it is to enter its space, resisting the self’s desire to control.

This is also the structure of democracy, entering the mind-space of other people to think equality. Indeed, this is the secret of unconditional ethics, not just doing good while doing well, sustaining the profit margin. Some of us call it the prayer to be haunted by the other and it is this secular prayer that the humanities teach. No hope of a just society if every generation is not persistently weaned from the basic human affects of greed, fear, and violence; disregarding race-class-gender apartheid. Unless there is persistent, sustained, and worldwide epistemic change, democracy and ethics cannot be desired and knowledge is managed for greed, fear, and violence.

In my imagined future anterior, nation-states have realized that this work is more crucial, especially in the face of planetarity, than the absurdity of the defense budget, where victory is determined by the number of people killed or diplomacy sustained by fear.

There a worldwide teacher-training budget takes first place, using and modifying the already-existing international civil society model, going forward in the world’s wealth of languages in primary and middle school, and changing the medium to a global lingua franca so that broad structural communications as citizen or politician can be sustained in adult life. Early familiarity with the multilingual world strikes a blow against confining identitarianism! All while using the contingent as instrument of learning. To quote what the 100-year old jazz player Marshall Allen learnt from his teachers and passes on to future players: “Play what you don’t know!”

This work is textured work, slow work, where you attempt to braid yourself with the weave of the other’s space. This is how democracy and ethics are other people. The humanities teacher can call such work reading. The word teacher is not class proud. I was interviewed by one of your journals and the journalist asked me how I thought of myself. I said: classroom teacher. From reading your cv, said the journalist, I should have thought you were an intellectual. If intellectuals are not teachers and teachers intellectuals, there is no help for the world.

And the humanities intellectual works at weaving. In so-called developed countries, emphasis is on structure, not texture. Structural thought, statistics, generalizations, are absolutely necessary, of course. But if not persistently supplemented by textural work, the practice of learning, knowledge will not be managed with justice on our mind. We will talk the talk, not walk the walk. In my classroom at Columbia, I encounter students who, with the humanities trivialized, have only been taught to control the text, to have a quick idea and make the text prove the point of that idea. Superpower self-exceptionalism combined with identity politics so that the abstract subject of global capital can be hidden, the North-in-the-South and the South-in-the-North can be forgotten and, given the harsh treatment of immigrants, identity politics can be seen as salutary.

It is with this group, smart and well-meaning, without any ethical training but top-down philanthropy, that our work begins. In that context, I think of what Jacques Derrida has called the new International, given that the old Internationale did not save the human race. In the place of vanguardist organization and paying for the party ticket, the possibility now is of a single teacher’s students, flung out into the world and time, where the classroom is the model for the building of collectivity. And, since the classroom is irreducible, and the idea is for everyone to be included, we must ask, again and again, “how many are we?”

Let me end with a summary description of my way of working that I recently sent to Frontier magazine, correcting what a young postdoc had put together:

I opened four schools in Purulia district in 1984. The schools were forcibly closed by the local landowner in 2006. Subsequently, I worked as selflessly as I could for 24 years, living among the Lohars in Birbhum. When they gave in to the seduction of capitalism and felt I was not needed any more, I left Birbhum and established 1, then 2, and now, by local demand perhaps 3, schools in another “backward” area. I insist that my method is to learn to learn from below, to learn from my mistakes, and that my motive is to see if the intuitions of democracy can be pedagogically transmitted to the children of the very poor and the work is to attempt to repay ancestral debt, although that is de facto impossible.

Time will not allow me to comment on how I attempt to introduce these subaltern children and teachers to the cartography of the climate-changed world. At Columbia I am kept on a tight leash by the corporate university, but there are still a handful of colleagues who encourage me to think, and students who are crazy enough to come to my classes. By rewarding me you reward them, my deliverable remains creating a general will for social justice, and it is in their name that this old pacifist thanks you, dear Crown Prince, dear colleagues, dear friends.

— Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Columbia University

Last edited:

Published:

Related content

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

The 2025 Holberg Prize is awarded to Indian scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak for her groundbreaking work in the fields of literary theory and philosophy.

Award Ceremony for the Holberg Prize and the Nils Klim Prize, 2025

The official Award Ceremony for the Holberg Prize and the Nils Klim Prize.

The 2025 Holberg Prize and the Nils Klim Prize Conferred

Today, HRH Crown Prince Haakon of Norway conferred the Holberg Prize upon Indian Professor Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.