On 4 June, Gayatri C. Spivak delivered the 2025 Holberg Lecture at the University Aula in Bergen. The lecture is published here in full.

An imperative is an urgent command, generally brought about by external circumstances. Today, natural violence creates an imperative to develop a planetary view of the future.

Introduction

Thank you for that unreal introduction! I want also to thank Minister of Research and Higher Education Sigrun Aasland, Madam Rector Margareth Hagen, Nils Klim Prize Laureate Daniela Alaattinoğlu, and members of the Holberg Committee and the Holberg Board. I want to thank Bjørn Enge Bertelsen and, above all, I want to welcome the audience.

Imperatives to Re-imagine the Future

Over the years, I have written a number of lectures beginning with the word “imperatives.” The first one was in 1997, almost 30 years ago, when I was asked by the Zurich-based Stiftung Dialogik to mark their change from concern with Holocaust survivors to concern with global asylum-seekers. Some years later, in 2018, I gave a lecture at Yunnan Normal University in China entitled “Imperatives to Reimagine the Silk Road.” There I gave a description of what not just I, but our group that we called “Rethinking Globality” wanted to suggest in the face of China’s Belt-and-Road initiative. I want to emphasize our collective agency because social “imperatives” of this sort are necessarily collective; and because one of the most important members of that collective, Professor Lakshmi Subramanyan, is with us today. Here, then, is what I said in China:

An imperative is an urgent command, generally brought about by external circumstances, and, in that particular case in Switzerland 21(now 28) years ago, external circumstances that had changed from a European to a global situation.

One of the magnificences attached to the original Chinese Silk Road enterprise was the great difficulty of actual physical movement through sometimes seemingly insurmountable terrain. Today the imperative to re-imagine that unifying idea comes from the fact that those physical difficulties have been dwarfed through the scientific achievements of global travel as well as networking and accessibility promoted by digitality, yet complicated by geopolitical violence. These have generated the new imperatives that we have proposed in the title accepted by all of you: imperatives to re-imagine the Silk Road.

Nearly 200 years ago, Karl Marx wrote these unforgettable words about the proletarian revolution:

Proletarian revolutions . . . constantly engage in self-criticism, and in repeated interruptions of their own course. They return to what has apparently already been accomplished in order to begin the task again; with merciless thoroughness they mock the inadequate, weak and wretched aspects of their first attempts; they seem to throw their opponent to the ground only to see him draw new strength from the earth and rise again before them, more colossal than ever; they shrink back again and again before the indeterminate immensity of their own goals, until the situation is created in which any retreat is impossible, and the conditions themselves cry out:

Hic Rhodus, hic salta! Here is the rose, dance here!

What Marx describes here is an imperative brought about by external circumstances. In globality, we confront such an imperative today. Natural violence has created an imperative to develop a planetary view of the future. Violence of nature: floods, storms, droughts, and wildfires; a river in the sky because the ozone layer becomes more and more impenetrable; plastic creating volcanic eruptions in the sea bottom; fossil fuel use destroying our air; cutting off of the Amazon rainforest and indeed deforestation of all sorts taking away clean air, pesticides and genetically engineered seeds poisoning the environment and human health; the seasons disappearing, tsunamis and mudslides, the list goes on. This is the imperative. And the task of the humanities is to re-arrange desires, so that we learn to want differently, rather than think smart capital to supplement degrowth. By the end of this lecture, this sentence will have been fleshed out.

All our plans encounter the limit of the future anterior – the past in the future – a certainty that something “will already have happened” related to the plans we are launching. Today that “past,” in whatever future we can imagine, calls forth geological history, so that some of us think: “system change,” rather than “climate change,” is required. This lecture discusses how the humanities can elaborate that change. “Elaborate” carries for me, a Europeanist comparativist, the Italian word “e-laborare” in its heart, a shadow of Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), the activist political philosopher who is one of my brothers. E-laborare, for Gramsci, means “to work out.” Therefore, for me, this lecture will imagine how the humanities can work out that systemic change. If, however, we think of the alternative system as an end rather than a means to a forever incomplete end ending in a planetary extinction written in geological history, we will spend our time defending the system rather than sustaining the (im)possible will to planetarity. (The parentheses indicate acknowledging that it is within a phenomenal impossibility that the conditions of possibility are lodged, and act accordingly. Therefore this lecture is dedicated to Ahmed Abu Rizik, teaching in a tent school under Gaza Great Minds.)

The humanities beyond the disciplines, in the teaching-and-learning mode, can elaborate the will to planetarity in many ways. In 1997, when I first thought planetarity, I believe now that I was also offering a more robust model of secularism, as an imagination of the transcendental, rather than a privatization of a belief in the supernatural; attendant upon religious history in Europe. Why else would I have written the following sentence?:

If to be human is also to be an occasional and discontinuous animator of what we call timing and spacing, like and unlike all living creatures, we provide for ourselves transcendental figurations of what we think is the origin of this animating gift of animation, if there is any: Mother, Nation, God, Nature. These are names of alterity, some more radical than others. Planet-thought opens up to embrace an inexhaustible taxonomy of such names including but not identical with animism as well as the spectral white mythology of post-rational science.[i]

Let us pause on the phrase “transcendental figuration.” Let us assume that the transcendental is, to follow Kant’s remarks to John Locke, that for which one cannot find legal proof, but without which one cannot access experience.[ii] It is not to be confused with the supernatural. It is to be noted that without the intuition of transcendentality, we can neither mourn nor judge. Belief is the least interesting part of the functioning of the mental instrument. Rather than be reduced to belief in the supernatural, the working of the transcendental should be constantly de-transcendentalized by the imagination. This is why I can think of what is called religion from within as poetry and why I work for training the imagination. My life has been dedicated to poetry and yet I certainly do not “believe” in it. One might say that the ethical must also imaginatively be saved from supernatural injunctions. And, in 2008, I had found an example of such transcendentalist ethical practice in Saradamani Mukhopadhyay.[iii]

My way of thinking moves, changing as the situation changes. Not all situational changes are sequential. In the case of planetarity as environmental damage, however, because of a disproportionately large practice of damaging policy, we seem surrendered to a fast-paced sequentiality; so that the epistemological question has changed to: How shall we integrate our re-imagining into a general activist position against the Anthropocene and acknowledge the modernity of the Fourth World? My smartphone has made me a member of B6, The Future of Philanthropic Investment! That is not the way and time will not let me develop this now.

Our imperative today may be the re-imagination of a completely fungible future rather than our perceived demands for inclusiveness and diversity alone. I speak of course in the name of my grandchildren that the imperative today is to re-imagine the possibility of an absurd future, a humanly random. We are now being played out by a greater planetary narrative where human accountability is way short of trivial. And, within that stepped-forward planetarity, we might as well imagine monstrosity as indistinguishable from the transcendental, for planetarity is not accessible to the value-form, liberal or “materialist.”

(Some years ago, in honor of Juliet Mitchell, I presented a paper on the transcendental as rape; it is a hard read, attempt it with a cup of tea when you are feeling expansive.)[iv] In the planetary, the question of human value is absurd. I normally teach, myself and my students, the distinction between historical responsibility and personal guilt. That distinction does not disappear, but becomes somewhat irrelevant when we are thrust into early planetarity by way of the Anthropocene unrestrained. I cite here a possibly resonant remark by an activist friend whom I greatly respected and whom Amitav Ghosh used in his The Hungry Tide: “I don’t want to lose faith in mankind and thereby lower my guilt quotient.”[v] What, then, about activism?

Let us now turn to a passage I composed in 2014:

in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. We must persistently educate ourselves into this peculiar mindset, of accepting the untranslatable even as we are programed to transgress it by “translating” into the mode of “acceptance.”[vi]

Here what is being described is an example of my usual understanding of activist method. Given that we have happened on a planet, activism can only be short-term, undertaken in terms of an immediate definition of “success.” We cannot philosophize about grand world-saving goals; yet, in persuading people, especially children, to rearrange their desires, we do need a bit of easy philosophy, poetic philosophy, remembering that poetry is not for belief. Something like this: think and feel, the whole world is my home, the whole world holds me up, including the firein its center and the water all the way down to the absurd ocean “floor” — in a sphere? No one can throw me away from the world, even if somehow I were to travel in space. Ownership is a made-up thing, we cannot own the whole world, or each one of us already “owns” it, in the only way that it can be owned, by contributing to the whole of it.

In my acceptance speech for the Holberg Prize, I will say that my method is to learn to learn from below, to learn from my mistakes. Imagining the (im)possibility of a planetary future, one is hung loose in the eternal immediacy of subaltern time. (I always use “subaltern” in the Gramscian sense: small social groups in the margins of history). I tried to describe subaltern time in my remarks at the Shanghai biennale some years ago, but not to much avail:

“Art has been so open to conceptualization millennially because one of its universal characteristics has been to transform the trace to sign that it sometimes forgets that it starts universalizing, into the possibility of accessing “a held-back [arrêté] time in which nothing resembling History can yet happen, an empty time and lived [subi] as empty: the time of their condition itself.”[vii]

The point might now be, in the face of the imminent destruction of the world as we know it, to pray to be accessed by this stationary time, since human accessibility to planetary time, measured in light years, can only be negated-as-affirmed by human calculus externally. Yet, the cracked and now hyper-real (“reality” with nothing real to back it up) story of historical advantages promising a future that has not been re-imagined, still leads my Columbia students to a sense of exceptionalist euphoria.[viii] One choice of course is to say go ahead, play at being custodians when what you are really doing is using the fact that the human is not nature. The human makes more than it needs. Anthropocene as mere excess. Whereas the earth is, by the seeming non-identity via agriculture (that apparent excess is how primitive accumulation enters into the first social formations, through the capitalization of land), identical with itself.

Placed in a situation of two humanities teacher jobs – one among the super power wishing to help the “marginalized” – one among the Bengali subalterns going from day to day, I can fill my work day with the effort (now for nothing) to push the students’ desire around, although it can no longer bring anything about. Could it ever? And why not learn to read? This is my self-set task for the U.S. student. Learn to read.

I try to get into a shared epistemic or imaginative space involving reader, text and me. I read the language of the text as reading-signals rather than semes (the difference is slight and hard to teach as habit rather than skill), somewhat more word-focused than I would like. I read four books this way, in class: Herland, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Sea-Wall, by Marguerite Duras; “Pterodactyl,” by Mahasweta Devi; and Oil on Water, by Helon Habila.

Perhaps the students learnt something about displacing themselves into the texts’ space. Perhaps a semester’s worth of practice will allow them to fall into this move if they are confronted by a situation that requires an ethical reflex; perhaps they were able to sense the bourgeois authors’ sense of the subaltern texture of climate change suffering. At least they learnt about Ken Saro-Wiwa’s brave resistance and death. I have always asked the question: does reading these books lead to good activism? Writing for you, I was obliged to say to myself, there is no activism any more, just holding action, giving up.

Professor Thangam Ravindranathan will not give up, she proposes a sort of reading which will make the novel useful for confronting climate change. She is combatting Amitav Ghosh’s complaint in The Great Derangement that

a turn that fiction took at a certain time in the countries that were then leading the way to the “Great Acceleration’ of the late twentieth century. . . . [T]he acceleration in carbon emissions and the turn away from the collective are both, in one sense, effects of that aspect of modernity that sees time (in Bruno Latour’s words)as ‘an irreversible arrow, as capitalization, as progress’.”[ix]

Ravindranathan calls her own way of reading “metabolic.” She is convinced that some “texts have been waiting for us, that is, waiting for readers able to reactivate dormant elements within them.”[x] I compare this to Toni Morrison’s remark “Invisible ink is what lies under, between, outside the lines, hidden until the right reader discovers it. . . . The reader who is ‘made for’ the book is the one attuned to the invisible ink.”[xi]

In Alain Robe- Grillet’s Jealousy, Ravindranathan refuses to consider “a notoriously lengthy description of patches and rows of banana trees covering the valley surrounding the house,” as a sign of the book’s failure, but rather “wondering . . . whether it is not the earth itself, or earthly matter, that is writing its way through our texts.” I am pleased that she

“conclude[s], now, with these words by Gayatri Spivak, ‘I have tried to use deconstruction as affirmative sabotage: do not excuse . . ., do not accuse . . ., but — enter that social formation that you are criticizing as thoroughly as you can […], enter to find in it a toehold that will allow you to turn the whole thing around to serve purposes other than its original self-comprehension.’”

In her quoted passage, I halt on the word “now.” Was her use of that word dependent on my presence in the audience, or her sense that she should mind the abstract space, or space of abstraction, outside of the humanly natural, as indeed has Gayatri Spivak, who thinks, now, that in pretty advanced planetarity, this turning around that is called “affirmative sabotage,” can promise no consequences. We cannot – except in the necessary mistake required for short-term survival – acknowledge “natural rights” beyond civil or human rights, as in this bold poem by John Trudell, the Santee Dakota poet:

“We must go/ beyond the arrogance/ of human rights./ We must go/ beyond the ignorance/ of civil rights./ We must step/ into the reality/ of natural rights./ Because all of/ the natural world/ has a right to existence/ and we are only/ a small part of it./ There can be/ no trade off.”[xii]

I repeat what I have said above: in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. But this too I have said: yet, in persuading people, especially children, to rearrange their desires, we do need a bit of easy philosophy, poetic philosophy, remembering that poetry is not for belief. I embrace John Trudell, then, as I embrace Thangam Ravindranathan, not because they are right, but because we need them.

In the elite humanities classroom, then, we learn to deny the human, except in short-term planning. Imagine a cut future, not a horizon but a porch. A consoling practice of reading, temporarily taken as permanent, beautifully articulated by Ravindranathan:

. . . a more haunting question, for me, concerns the status of the “knowing” of a novel that carries inscriptions of intensivities or forms of degradation not necessarily understood as such in its time—is this knowledge located in the characters, the narrator, the author, the “text,” or is it of a different (earthly/unearthly) order altogether? This exorbitance has been for me one of the principal lessons of deconstruction, and I have found myself wondering at times, during this reflection, whether it is not the earth itself, or earthly matter, that is writing its way through our texts.

To make the planet instrumentalize us into planetarity – “the earth itself … writing its way through our texts” – the most moving desire to confront the irrelevance of the human in the planetary system. Ravindranathan signals to us that this is just noematic in the sense of the European philosopher Husserl who, at the end of his life, had tried to confront the irrelevance of the Jew for Christian Europe – represented by his own former research assistant Martin Heidegger, who locked him out of the library and out of his own office. I “found myself wondering at times,” she writes, occasionally, in other words; “found myself,” not necessarily through the logic of intentional deliberation, in other words; and, even then, not always, but only occasionally “during this reflection,” and not in an assertive but in a questioning mode – “whether it is not the earth itself,” that writes its way through “our texts,” emphasis mine. Yet she does affirm, through Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

“And so let me conclude, now,” — in other words, she may have a different conclusion on the occasion of the finished book – with these words by Gayatri Spivak, “I have tried to use deconstruction as affirmative sabotage: do not excuse (saying “art can heal”), do not accuse (saying “museum is colonial”), but–enter that social formation that you are criticizing as thoroughly as you can […], enter to find in it a toehold that will allow you to turn the whole thing around to serve purposes other than its original self-comprehension (emphasis mine).

Turn around the original self-comprehension of the planetary system. The impossible task of unearthly readings. The (im)possible task of the humanities, teaching reading, beyond the disciplines.

So much for the Research 1 university where I teach, hoping to produce collective policy intervention as we read our world as earth, beyond the disciplines. What about the ungeneralizable subaltern schools where I also teach? These people have mostly not ever moved out of the environs of their villages, never seen an ocean or even a lake, never seen a hill or a mountain and, in their state-issued textbook, the earth and the sun and the planets are small balls, and the earth, seemingly larger than the sun, is described as spinning like a top, which relates not at all to their experience, so there is no cartographic sense at all. I wish I could go into detail here about how we sit on the ground together and “sense” the earth’s (im)possible roundness, and “sense” ourselves into its slow revolution and, with the help of my friends and relatives on the other side, learn heliocentric day and night at once via google video. They remind themselves of gravity, since these friends are hanging upside down on the other side of the globe and yet not falling off. But that still does not bring us into planetarity, or show its discontinuous alterity.

They do not read books, apart from the textbooks from which they teach and from which they passed their exams in the past. I gave my supervisor, Ujjwal Lohar, a man in his late forties, who has studied up to class seven in the state system and with whom I have worked for over twenty years, and who had never read a book, a book on science prepared in Bengali for imagined high school students by diasporic Bengali scientists in the San Francisco bay area in the United States. He read it and said to me: “Sister, outer space is something else!”

I prepared a tiny video clip for him, subtitled in Bengali, and shared it with my two teachers Sundari Kisku and Budin Hembrom, and with Anirban Bhattacharjee, my assistant director. They had seen pictures of the round earth on their smartphones, supplied by me (Anirban bought his own). Now they saw it through human eyes. I invited them to imagine that outer space was crosshatched by lines of force that made the planets move, and discussed European antiquity’s imagination of the music of the spheres. I talked to them a lot about the intolerable heat of our fiery young sun and I sent them a video of the music of the sun.

Spacewalk

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1068RYin-_ylsxmEDYP4qnixoAWd7aRjH/view?usp=sharing [xiii]

Sun’s music

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1v1R3ZISvDIK8R5HZ2zSCXOB2qRZYG25-/view?usp=drive_link

Sundari was intrigued by the idea of an ocean floor in a sphere, and with the idea of fire there as well. She asked why, if the earth floated in water, there was such water shortage? So I found a tiny clip of volcanoes under water, made a subtitle or two and am waiting to discuss it. For water shortage I showed her Namibian women learning to live with drought rather than offer an explanation. She will learn to learn if I can supply initializing answers. Here are my two attempts:

Underwater volcanoes

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Met5j_43N3U8dTzbujKQobj19ovrGtBI/view?usp=drive_link

Namibia

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1UxEGoDIiz_bClF3rneYs_x89CWxkhilv/view?usp=sharing

They are so far below the NGO radar that they are not often bothered by Human Rights advocates. But even when they are, since they have not been brought up with the liberal self-sense of individuals with inalienable rights, they are furthest from the subjectship which would approach the subjectship of human rights. Therefore, human rights talk for them is not very different from top-down philanthropy with no structural support. To be “understood,” it would ask for a sustained labor in subject formation that must be undertaken by way of an education that must not look to succeed as a deliverable, but rather continued persistently from generation to generation. This is my task as I understood it in 2020. But today it must be performed in the imagining of temporary-for-permanent. Within the task as I understood it in 2020, I wanted to give them through developing educational technique, a sense of responsibility for saving their home, the whole world, rather than always be told they are victims. They must now learn the temporary-for-permanent mind-set, within which this unusual lesson of responsibility rather than guilt must be learned. This is learned more easily by them than by us, because the insubstantiality of life is their daily sense of things.

Even a year ago, I thought long-term, as I wrote: We have been copying bits of television programs that show climate disasters that speak to the subalterns who are my students, teachers and supervisors. We have been subtitling them in Bengali.

When the program is copied, we make a cut that has been accessible to the subaltern group that we know. And then, per yet another new thought, we are thinking of putting subtitles in as many subaltern languages as we can access. This can of course be magically broad. But there is no subtitling without access also to actual subaltern groups. Our standards will be tough, since we undoubtedly will not have much money. And our goal: use these clips, without interpreters, to make the subaltern groups feel the responsibility for looking after Mother Earth rather than only be defined as victims. A huge collective project. Produce this worldly subject. Resonate with Gramsci, Du Bois, and Tushar Kanjilal, my dear friend, now dead.

Even then, there was a problem. Those who were most eager to join the project had no plan to get to know subaltern groups texturally and assured me that they could offer me databases of appropriate video clips; not realizing that my task had been to imagine the working of damaged cognitive machines so that I could choose clips that would speak to them. But the world’s wealth of subaltern languages would have been a challenge, not a problem. Within this non-context, then, the imperative to learn to withhold imagining a long-term future, let me show two clips that have spoken to them, the one about water, the second, on plastics that was a direct reminder of their responsibility to rearrange behavior:

Water

https://drive.google.com/file/d/14LZY_To4sctbKRauZ5cfe7dFqRIkIvct/view?usp=drive_link

Plastic

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JVxBUYuL340TNtxKLqUcOXEZ_rjXuaBS/view?usp=drive_link

At a certain point, they had asked me to go through the earth lesson with the entire village, guardians included. I now think it was because they felt this knowledge should be available to their contemporaries, their elders. The first time around, I had thought their request unreasonable and had an earth-class, beginning with the youngest, that did not amount to much. Writing for you, putting Ravindranathan and my Santhal teachers together, I have learnt from my mistake, and we will see in July, if we can perhaps redo the class. If middle-class readers of international novels are taught to wonder if the earth speaks through their texts, these men (and some women) must be able to protect themselves from the impossibility of imagining a future by claiming the earth calling them, in some way.

The goal of these schools had been to see if a pedagogy could be developed that would insert the intuitions of democracy in subaltern children. I now can see that the everyday sharing textured practice of democratic habit-formation has entered their agency-concerns. Remembering the temporary-as-permanent imperative, our attempt to do the earth-class with a group of generally illiterate and poor adults, will be a challenging response to this imperative seeming to invite (impose?) a double bind.

In 2023, Professor Denise Ferrera Da Silva at New York University invited me to a group conversation about democracy. I asked my village teachers to send me videos. I choose two out of the few they sent.

The Woman

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CyjHDzoSWkLFIhet9r4JQdKKdaulyrN-/view?

The Man

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GOm5bp9A67px8EbjssAiE8FGw2lwUBPP/view?usp=drive_link

They may not be verifiably representative, but by way of fiction, my teachers sent me a message: we do not know what it is to vote. The man says so openly and the woman is not asked. The man might have been lying or joking, and the woman might have been able to explain what it is to vote. That is not the point. The point is that the videographic fiction sends us the message: teach us democracy; further, that they know enough to know that they do not know enough. Structural democracy is planning for the short-term future, until the next elections. Possible even in these trivialized times, even if, the time for textural democracy, in the robust, epistemologically felicitous sense of democracy for other people, democracy as persistent revolution, may well be over as mere human greed unleashes a wounded planetarity. Think of the implications of this, please, as I thank you and sit down.

©Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Notes

[i] Willi Goetschel, ed., Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Planet/Imperative zur Neuerfindung des Planeten (Passagen: Vienna, 1999), p. 46.

[ii] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, tr. Paul Guyer and Allan Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, [1787] 1998), p.221.

[iii] “Imagination, not Culture: A Singular Example,” unpublished William James Lecture, Harvard Divinity School, April 10, 2008.

[iv] “Crimes of Identity” in Juliet Mitchell and the Lateral Axis: Twenty-First-Century Psychoanalysis and Feminism, ed. Robbie Duschinsky and Susan Walker (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). Illustrations supplied upon request.

[v] Ghosh, The Hungry Tide (Boston: Mariner, 2005); the quoted sentence is from Tushar Kanjilal, Who Killed Sunderbans: Essays on Environment, Development and Survival, tr. Abhijit Sen (Kolkata: Sampark, 2022), p.79.

[vi] Barbara Cassin et al., Dictionary of the Untranslatables (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 1223.

[vii] Louis Althusser, For Marx, tr. Ben Brewster (New York: Verso, [1065]2005), p. 136; translation modified. Particularly irritating is “situation” for “condition”. For “situation” is the material details of the phenomenality of the phenomenon, whereas “condition” here is probably a shortcut for condition of possibility of the phenomenon.

[viii] For “hyper-real,” see Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra & Simulation, tr. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994) p. 22,78

[ix] Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Gurgaon: Penguin, 2016), p. 106

[x] All passages quoted by me from Thangam Ravindranathan, are to be found in “The Banana and the Sovereign,” in Unearthly Literature (forthcoming).

[xi] Toni Morrison, “Invisible Ink: Reading the Writing and Writing the Reading”, The Source of Self Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019), p. 348.

[xii] Flyer distributed by the Native American Rights Fund.

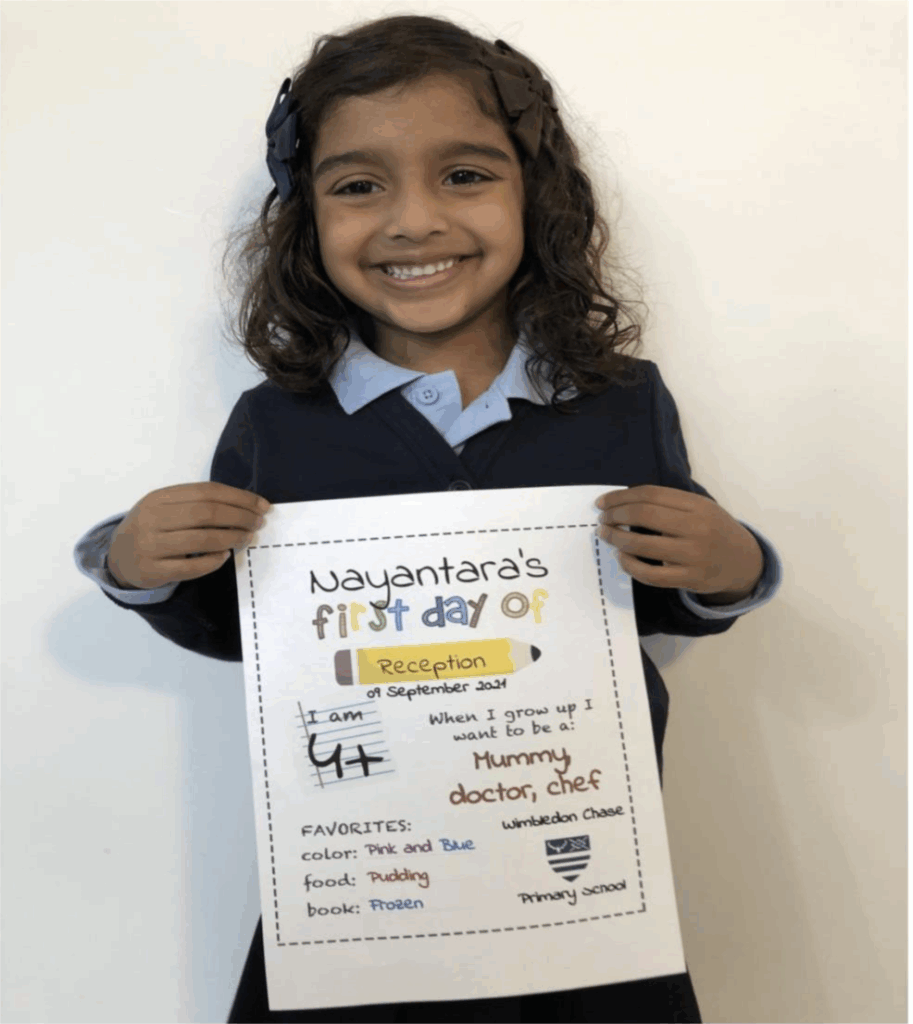

[xiii] All but my great-niece’s photo, and the last two slides in the essay, are from BBC News. Permission has been solicited.

Last edited:

Published:

Facts

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (b. 1942) was awarded the 2025 Holberg Prize for her groundbreaking work in the fields of literary theory and philosophy. Spivak is University Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University and is considered one of the most influential global intellectuals of our time, and she has shaped literary criticism and philosophy since the 1970s. Spivak has authored nine books and edited and translated many more. Her scholarship has been translated into well over twenty languages. She has also taught and lectured in more than fifty countries.